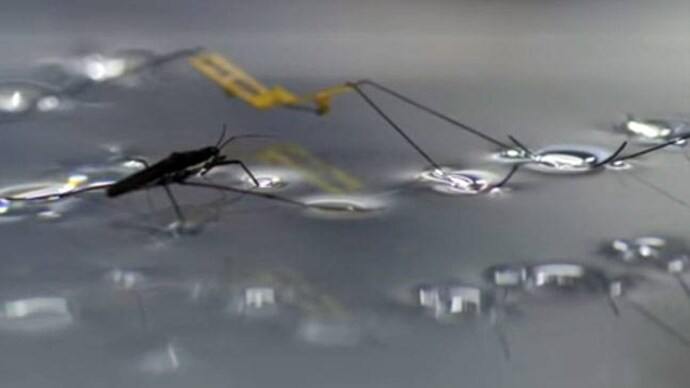

Rhagovelia water striders

The particular fan-like propellers of the Rhagovelia water striders, which enable them to glide across swift streams, open and close passively, like a paintbrush, ten times faster than the blink of an eye, according to a team of researchers from the University of California, Berkeley, the Georgia Institute of Technology, and Anjou University in South Korea. Motivated by this biological breakthrough, the group created a ground-breaking insect-scale robot with specially designed self-morphing fans that imitate the nimble motions of Rhagovelia insects. This work demonstrates how the design and function of a biological adaption influenced by natural selection can improve the endurance and mobility of bioengineered robots and water striders without adding to energy expenses.

The millimeter-sized, semiaquatic Rhagovelia water striders are distinct from other water striders due to the usage of specialized fan-like structures on their propulsion legs, which allow for quick twists and bursts of speed.

When I first noticed ripple bugs during the epidemic while working as a postdoc at Kennesaw State University, I was fascinated. Victor Ortega-Jimenez, a main author of the study and an integrative biologist currently at the University of California, Berkeley, stated. Rhahovelia bugs were different from the huge Gerridae water striders from unstable waters whose jumping abilities Ortega-Jimenez had previously examined. “These small insects looked like flying insects because they were skimming and rotating so quickly across the surface of turbulent streams. What do they do? It took almost five years of amazing teamwork to find the answer to that question, which lingered with me.

It was previously thought that the only source of power for these fans was muscular activity. But according to a study that was published in Science on August 21, Rhagovelia’s flat, ribbon-shaped fans may passively change shape without the need for muscular exertion by utilizing surface tension and elastic forces.

“Observing for the first time an isolated fan passively expanding almost instantaneously upon contact with a water droplet was entirely unexpected,” Dr. Ortega-Jimenez remarked.

The bugs can make sharp turns in just 50 milliseconds and travel at up to 120 body lengths per second thanks to their amazing combination of stiffness during propulsion and collapsibility during leg recovery, which rivals the flying flies’ quick aerial acrobatics.

I witnessed a genuine discovery that was right in front of me. We frequently believe that science is a single, brilliant sport, but this couldn’t be further from the reality. To study nature and create new bioinspired technology, interdisciplinary teams of inquisitive scientists collaborate across boundaries and specialties. This is the essence of modern science.

Next-generation water strider robot Rhagobot is born.

It was quite difficult to make an insect-sized robot that was modeled after ripple bugs, especially since the fan’s microstructural design was still unknown. The solution to this puzzle was discovered by Dr. Dongjin Kim and Professor Je-Sung of Ajou University, who used a scanning electron microscope to take high-resolution pictures of the fan.

They were able to reconstruct this natural propulsion system in a robotic version by using these insights to decipher its structural foundation and function. The end result was the development of a self-deploying one milligram elastocapillary fan that was incorporated into a robot the size of an insect. Tests using both real insects and robotic prototypes have confirmed that this microrobot can perform improved propulsion, braking, and maneuvering.

Evidence indicates that cormorants and whirligig beetles use their webbed feet and hairy legs, respectively, to create hydrodynamic lift for swimming propulsion, making this option intriguing.

Along with these vortices, Rhagovelia bugs also generate strong bow waves at the front of their bodies and symmetrical capillary waves during leg propulsion, which seem to help generate thrust.